Old content

This post is over 3 years old. Some of the content might be out of date. If your after something more up date, check out our latest posts. If you want to find out more about the content on this page, contact us.

A Breath of Sound was part of a community engagement programme City Arts developed for World Event Young Artists. WEYA was Nottingham’s flagship Cultural Olympiad Event, bringing over 1,000 artists from across the world for ten days to exhibit, perform, display, play, collaborate and share. City Arts created an extensive programme of work responding to the festival, bringing creative opportunities to communities and developing new and exciting participatory events for the festival.

Our programme included Kurdish/South Asian collaboration with community participants; 45 metres of silk marked by every artist in the festival; a new geodesic pop-up venue, the dome, and a piece of mass participation singing for Nottingham’s Royal Centre.

As part of this programme, I led the production of ‘A Breath of Sound’. This was inspired by an astonishing performance, The Air We Breathe from Dutch composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven. This was a performance from a group of singers moving between the stage and the audience, with final part of the show folding the audience into the piece, creating a musical environment of resonance and inclusion.

I invited Merlijn to be part of our WEYA programme. I then approached the Nottingham Royal Centre as a partner for the project. The Royal Centre is the biggest venue in the city, and also one of the best designed acoustic spaces in the country, offering us a unique opportunity to play with sonics, space and environment.

Two singers from Nottingham helped to recruit participants, Tim Lole and Neil Allen. We set up singing workshops, started researching choirs and music groups, went on the radio to promote the event, and ultimately held a sharing day for groups and individuals. We recruited eight choirs for this day, with each group sharing their work and playing with exercises and elements sent over by Merlijn.

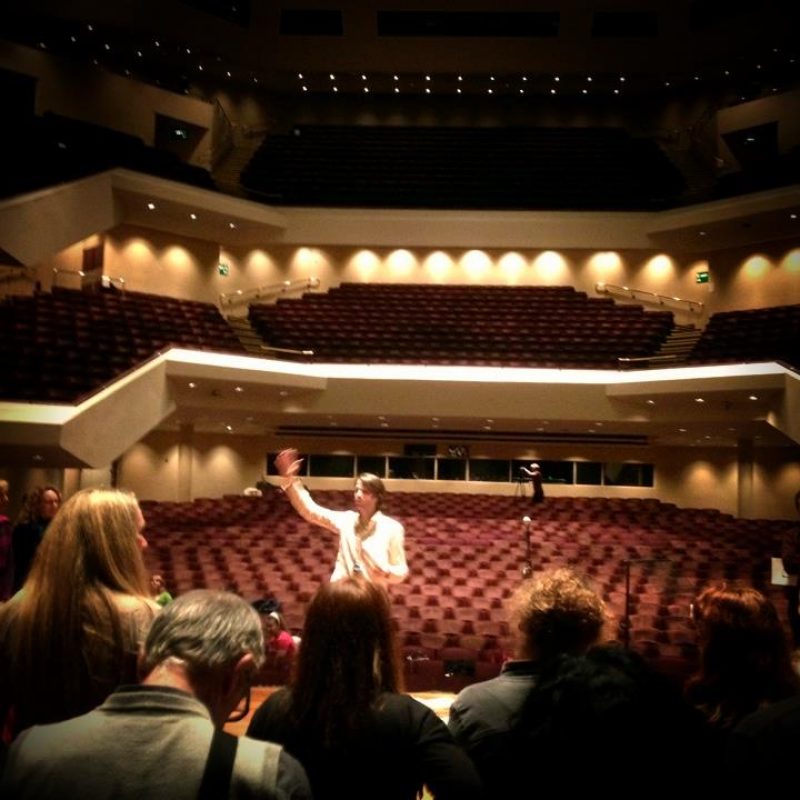

Merlijn came to Nottingham for rehearsals a week before the festival opened. He designed the rehearsals for the piece to fall into place over that period, structured round three tiers of participant – lead soloists, group leaders and choirs. The performance was based around synchronised stop-watches, with each group being given a breakdown of their part, in minute by minute sections. Within this structure, groups could improvise and be playful. For the performance, generally, no one was on stage, choirs were placed around the theatre, each with a soloist and group leader. We also worked with a number of schools; partly to open out the experience, and partly a calculated move as many children equals many parents, which equals an audience.

The school groups and the community groups only came together on the day of the event. Part of the overall concept of the performance was a sense of spontaneity and improvisation, however, in hindsight a longer rehearsal period would have been preferable for some groups. The volume of children involved was slightly de-stabilising. In the precious pre-performance moments, when the main aim is to pull together performers to share a moment of focus and intention, we were suddenly crowd managing, trying to support anxious teachers and excited children.

It was within this environment that the performance seemed to take on a life of its own. Stop watches were synchronised, which meant the official start, the doors were opened and the audience came in, suddenly I was huddled with my group of singers working our way through 60 slow long minutes, creating a vocal sonic experience rippling across the space.

Watch Ben Wigley’s film of the event, made for The Space:

Going through the feedback from participants and audience, as well as my own response, this was not an easy piece of work to experience. In many ways, it was more demanding for the audience than those taking part. Although participants were challenged and pushed, the rehearsal process supported them to develop a bond with each other and Merlijn that enabled them to take the leap of faith required. The audience however, had come in cold, and perhaps needed more guidance to access the work. The usual rules of performance did not apply– there were no performers on stage, there was no obvious starting point, there was no focal point, with the singers being spread all across the venue. As a result, the audience never seemed to settle. Some people left, children ran up and down the aisles, some people thought it was pretentious, some people thought it was bold and brave, some people were elated, and others glad when it was over.

Taking a moment to reflect now that some time has passed, I can make some observations. I was surprised how avant-garde the outcome was, and felt keenly the challenge of the work as I generally strive to make work that is accessible at many levels in order to support engagement. But therein is an important question. Is the aim for participatory and community work to be ‘easy’, or is this a dis-service, both to the art and the communities engaging in it? The participatory sector delivers at many levels, both creatively and socially; it responds to the creative ambitions of the people involved, helps individuals, offers therapy, gives people somewhere to go, supports career choices, brings people together, even fills a secular gap. And is not all art participatory at some level – the very act of going and seeing being a gesture of joining in. So is it a rare thing to create work that aims for mass participation that is also difficult?

Participation, for me, is for people to be actively engaged in a creative process, and it is the role of the artist to make that process as stimulating, engaging and responsive as possible. It is the role of a middle agent, such as City Arts, to marry those two elements together, the people and the art, and to some extent understand the wider role that the project can deliver. The outcome of these collaborations creates art that could only happen within this framework, and with the input of people, at whatever level they chose to engage. Opening up this creative dialogue with people who may not regularly access the cultural offer is an important part of what City Arts does. The relationship between the artist and the group will make the work, but how individuals respond is up to them.